Links to PART 1, PART 2, and PART 3

The most significant person in my childhood was my dad. He had the biggest impact on me. He was highly abusive but I don’t want to go into what he did to me. This is more a little bit about who he was, and a little bit about why he was. My mum wasn’t around after the age of about 7, so she didn’t have as much as an impact on who I am, unless you count the effect of my mum’s absence – but to be honest I’m still working that one out myself. For now, here’s my dad.

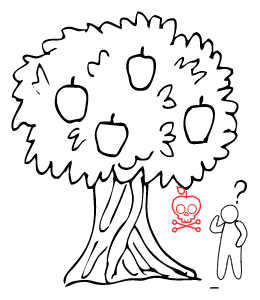

Dad swiped at anything that tried to control him. He ran head first, screaming, deep into his inner forest without a map to find his way out. Maybe he was troubled from the beginning. I grew used to hearing, ‘Well, you know what your dad’s like.’

Dad sulked a lot as a child. When driven to see Big Nan (his great Gran) the car would pull up outside the house and he’d refuse to leave it under any circumstances. He sulked until Big Nan came to coax him into the house. Little Nan told this story to demonstrate Dad’s inborn stubbornness. To support the ‘Well, you know what your dad’s like’ attitude. Dad told the story to demonstrate how hard done by he’d been his whole life. To support the idea that his “resilience” had remained strong.

Dad was the middle child of three brothers. His older brother was Jez, his younger brother, David. Jez and Dad shared a bitter hatred for each other. They fought often, yet at times they fought alongside each other as allies. Family first, as they say. Dad was anti-authoritarian and violent. He learned violence from his mentors. His uncle Robert was notoriously violent, Big Grandad was violent. His mother’s lovers were violent, including his own father who Dad never knew. Little Nan was violent. She’d use her wooden Scholl sandals as weapons when he or Jez earned a significant scolding. Dad told me many times, almost with glee, about the wooden Scholl. Maybe he felt the beatings he got as a child were an initiation. A ritual he’d survived that had made him a harder person. Beatings can become a rite of passage in the hindsight of those traumatised by receiving them.

I think Dad’s whole attitude to life was formed in his early years and he never looked back. For a lot of my upbringing he acted like that child sulking in the back of the car. Dad’s stories of rebellion against the schools he was regularly expelled from were always told with a sense of accomplishment, virility, and dark reminiscence. As though he received a source of power from reciting them. They were like little spells he kept locked up inside himself.

There was a certain story he loved to tell, and it caused me particular emotional conflict. It was the story of the cello-playing English teacher. Dad had been in English class with his head down, doodling in the exercise book he should have been working in. Doodling was something he was good at, English wasn’t. The teacher’s desk was at the front of the room on an elevated little platform. Next to her desk was an upright cello on a stand. The cello was the teacher’s pride and joy, and she’d sometimes play it at break times rather than going to get a cup of tea or some fresh air. The ghostly music would be heard echoing down the halls.

She was walking around the room checking that work was being done. Dad was oblivious. When she got to Dad she pulled hard on the spiky, gelled hair just above his ear. This was the seventies so this type of assault, and worse, wasn’t uncommon in classrooms. Dad yelped, spun around and snarled. He was a punk. He had safety pins in the lapels of his inside-out blazer, a tie with the end cut off, and an attitude to match. He even had drawing pins pointing up through the shoulder pads of his blazer so if a teacher grabbed his shoulder in a kind of ‘caught yer now, laddy’ way, they’d regret it.

The teacher told him to get on with his work. He told her sternly not to pull his hair. She smirked and went and sat back behind her desk. Dad watched her get on with whatever she was doing then got his head down to doodling. A few minutes later, back in his own little world, he felt the shooting pain of his hair being pulled. Vexed, Dad told the teacher she’d be sorry if she did again. They stared at each other. Dad began to doodle in his book, an invitation for her to try it. She did. Dad launched himself to his feet, knocking the teacher backwards, and sprinted down the aisle of chairs. Dad jumped, the teacher screamed, Dad flew through the air and smashed feet first through the cello. Leaving it in splinters on the floor. He stood up, brushed himself off and walked out, leaving the teacher shocked and in floods of tears. She had to take time off work. When she returned she brought no cello, and the students no longer heard the beautiful eeriness of the cello from behind her door.

This story has always left me conflicted. I suppose they were both wrong in their actions. I can feel the burning anger Dad felt at being humiliated and abused, and the terrible loss of the teacher who watched something that meant so much to her so utterly destroyed. I could never resolve this conflict and still can’t.

The stories Dad usually told were about man vs the world. It was him against everybody else. He’d tell me how I had to fight for what I wanted in this life, not take any shit from anyone. He wanted to teach me to be a wolf and not a sheep, how to assert my masculinity by having lots of female lovers. How to be feared. All things he wanted for himself. Unfortunately for me he inadvertently taught me that the world is a scary and violent place. That it didn’t matter who I wanted to be, I was going to have to be hard. A big hard manly man. But I wasn’t hard, and I secretly thought girl’s stuff and the colour pink were quite nice.

Dad’s whole persona was built around being visually and verbally intimidating. He adopted the punk persona, snarled at anyone who stared. He knew how to fight using the energy and anger he was full of. He looked up to Sid Vicious and Johnny Rotten. Their music, their image. He rebelled against the systems of authority that were trying to oppress him. And I don’t blame him. The support he truly needed for his healthy development was never there, and he didn’t want to be scared, he wanted to be the scary one. So when school tried to intimidate him into learning he fought back, like he was taught to.

Dad did have a creative side. He could draw. When I was little he’d spend hours drawing using pen or pencil to create amazing pictures of deformed faces and bodies with intricate, almost tribal patterns swirling about the page. I now know he did this when he was on speed. Speed gives a person bountiful energy, and when alone, spectacular focus. People who take drugs often recall how spotlessly clean their house would be after a speed binge. On some occasions when speeding he sat from late at night into morning and sketched until his pictures were immaculate.

He’d had the pursuit for creativity killed by school. One time, in design and technology, he was set homework. The task was to write something creative about technology. Normally he’d never do homework, but he was interested in this so he gave it a go. He wrote a poem about nuclear war. Decades later he could remember it off by heart and would recite it to me. It was simple but effective, and clever. The last line was, ‘Four minutes to be precise, before they fire the nuclear device.’ It was about eight lines long and rhythmic. The teacher was so impressed by the poem that he believed Dad couldn’t have possibly written it himself and couldn’t have a mark for his homework. Dad didn’t write any more poems after that.

In stories forests can be representative of dark emotions, the unknown, the unconscious, new challenges and acquiring new knowledge from the past. In the forest a fool can start his journey to become a knight, someone lost can find colourful companions, they might even meet the wolf. If they’re not careful they might become the wolf. We all have our forests, we all travel to them from time to time. Some more than others. Some use the forest as a place to settle scores, a place to battle ogres and bring back gold – the gold of artistry, the gold of knowledge, the gold of wisdom.

Dad never left his forest. His past shaped him in ways he could never acknowledge and his resentment of the past became him. He ran in circles with no pen in hand to scrawl a map of the thick woodland. Uninterested in addressing what might lie behind his hurt and his fury he lashed out at anything he saw as a threat, or prey. King in his forest. To leave his forest would mean giving up his throne, and there was nothing Dad disliked more than feeling vulnerable. To be part of his life I had to live in his forest, under his reign. Sometimes he took me under his wing, sometimes I was his prey. His insignia is forever branded within my bones.

Just another aging, traumatised millennial. Exploring trauma, mental health, addiction and "recovery" through the voice of lived experience.

[…] Links to PART 1, PART 2, and PART 3 […]